Welcome to “Theology That Becomes Biography”

Welcome to the relaunch of my personal resource website, danielrhyde.com. I want to thank the small army of friends who have labored to bring my site back to the world, including barzonDESIGN for the amazing logo and Simply Theology for the site design! Now, onto the new subtitle of the site: Theology That Becomes Biography.

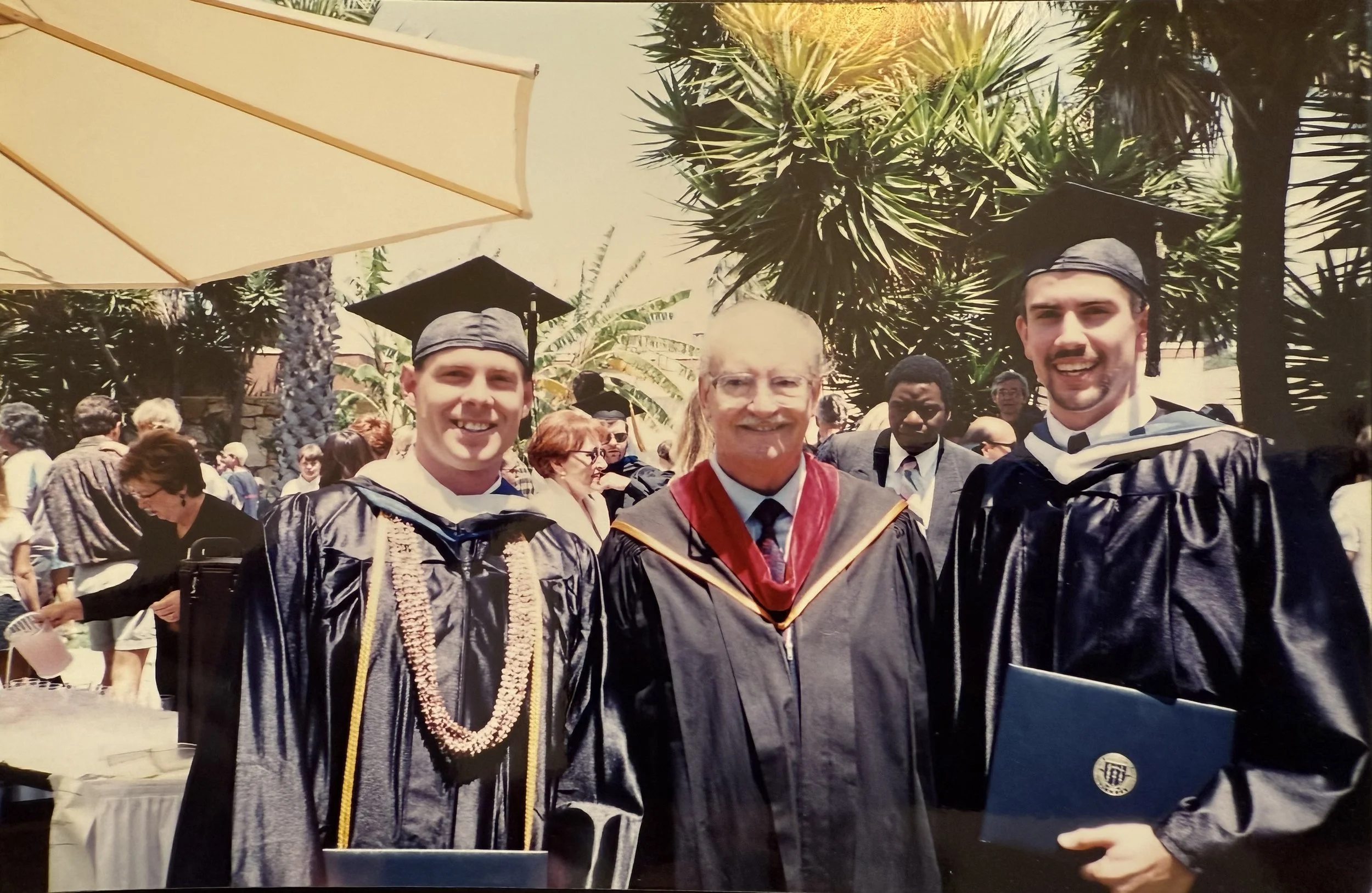

My influential college professor, Ronald Wright, always said in class: “Theology that does not become biography is wishful thinking.”

I don’t recall him discussing the question of theological prolegomena in terms of whether theology is more speculative or practical, but I later came to learn that his slogan was a result of hundreds of years of Christian reflection. Thomas Aquinas (1225–74) asked this question in his magnum opus, Summa Theologiae 1a.1.4. His conclusion was that theology is a mixed discipline of the speculative and practical, but he did come down on it being more contemplative or intellectual. On the other side of this debate was John Duns Scotus (ca. 1265/66–1308), who said theology was practical and emphasized the will. Hence, in history, this debate led to a difference between the kind of theology the Dominicans (intellectualism) were known for versus that of the Jesuits (voluntarism).

By the time of the Reformation, this issue of theology being either contemplative or practical or a discipline primarily of the intellect or of the will was long discussed. Reformed theologians all agreed that theology was both speculative/contemplative and practical; they only differed on where the emphasis was to be placed. I’m taking the position also that theology is both, with an emphasis on the practical: our intellectual, contemplative theology is for the purpose of our wills being moved to the practical: love for God and neighbor. In the words of Richard A. Muller, “Aquinas assumes that theology is primarily contemplative whereas Scotus defines theology as practical. The Reformed tended toward a compromise that respect the balance of intellect and will but recognized the underlying soteriological issue as voluntaristic and, therefore, defined theology as both speculative and practical with emphasis on the practical” [God, Creation, and Providence in the Thought of Jacob Arminius: Sources and Directions of Scholastic Protestantism in the Era of Early Orthodoxy (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1991), 79]. As the influential French Huguenot philosopher, Petrus Ramus (1515–72), said, “Theology is the doctrine of living well” [Commentariorum de Religione Christiana, Libri quatuor (Frankfurt, 1576), 1.1]. William Perkins (1558–1602), said “the bodie of Scripture, is a doctrine sufficiente to live well” and “theologie, is the science of living blessedly for ever” [Armilla Aurea, id est, Theologiae Descriptio, Mirandam Seriem causarum & Salutis & Damnationis iuxta Verbum Dei proponens (Basel, 1596), chap. 1; A Golden Chaine, or the Description of Theologie, Containing the Order of the Causes of Salvation and Damnation, According to Gods Word (Edinburgh, 1592), chap. 1]. Finally, William Ames (1576–1633) said, “Theology is the doctrine or teaching of living to God” [Medulla Sacrosanctae Theologiae (London, 1629)/The Marrow of Theology, 1.1.1].

As we read the Bible, we move from creation to rebellion to redemption to consummation. God made us for himself and for us to live with him in the blessedness of his life. We’ve rebelled (“sinned”) against him and have sought our own life in ourselves. Yet, God loves us and promised a Redeemer to bring us redemption from our sins and reconciliation with him. This leads us to the consummation, the end of all things of living with him in blessedness forever. This intellectual theologizing should affect us in the here and now; thus, it is theology that becomes biography!